In the Bahamas, at some point in its not too distant past, the native fete of John Canoe, the dance of the Merry Andrew, had been given a curious spelling. It became J-U-N-K-A-N-O-O! This was not the only unique variation, others had taken liberties like Jonkunnu, Jankunu and even John Kuner.

For a large part of World War II, between the years 1941 to 1945, John Canoe, in Nassau, was cancelled. There was nothing to celebrate while war raged. Tourist travel had decreased, Bahamian soldiers were fighting and dying abroad, the revenues of the colony were precarious to say the least, and many working class labourers were in America on the Contract.

The festival tradition of John Canoe wouldn’t be revived again until 1947. In 1951, Jamaica was reviving its John Canoe festival as well. Oh do let’s write it by its original spelling, for the moment at least. The unique Bahamian spelling of “Junkanoo” was a clever derivation, to give a particularly distinctive flavour, to the Nassau offering, as opposed to the Jamaican, Belize and other offerings, at the time.

As late as 1960, local newspapers were still ambivalent towards the new creative spelling of it, and referred to its original wording, it as well as its now unique Bahamian creation.

(December 18, 1947 Miami Daily News)

By 1947, when it came back from an almost cultural extinction, Bahamian government officials, realised that it was better to swim with the tide, rather than against it. John Canoe would be used as a much needed element, to draw tourists, to the islands.

(December 15, 1935, Brooklyn Daily News)

In John Canoe’s local history, arguably since the late 1800s, there were some, more than some, who wished that the tradition of the negro street carnival at Christmas time, in Nassau, would die a natural death, as many customs often do.

(August 1, 1894, The Louisville Courier)

Negroes had the August 1, Emancipation Day celebrations, and now it seemed that Christmas, the sacred religious time and New Year’s had been usurped as well.

(December 18, 1947, Miami Daily News)

John Canoe only really became interesting after the end of slavery. Waves of interest began in what the Negro did during leisure time, his unique music, his health, diet, spending habits and quite particularly, who they worshipped in their minds and hearts. It was very important, to all who pondered such things, in the late 1800s in the liberated English colonies, that the emancipated negro, did not revert back to his primitive, pagan way of life founded in Africa. John Canoe was viewed as African witchcraft and an extension somehow of Obeahism.

Scientists, artists, newspaper columnists, musicians, composers, authors and social researchers drew new readership for articles which centred on the then pressing question of the future fate of the now freed negro. Across the western world, anthropological observations on the life of the Negro suddenly became in vogue. The late 19th and early 20th century was attempting to understand its past, and role it played in the lives of the descendants of transported and enslaved Africans. For the John Canoe masqueraders with all its strangeness, rather than attempting to offer anything plausible, it was all put down to ‘they brought it with them.’

How did African slaves, from different regions, different languages, different allegiances, different everything, many sold by other African tribes, somehow manage to hone in on one man and make his life, real or mythical, a central story in their own lives for over 200 years?

How did this happen?

Who carried the message?

If John Canoe was all that myth said he was, why was it encouraged, or at the very least ignored by slave masters?

Was John Canoe something else altogether and in fact had nothing to do with Africa?

Was John Canoe a slave adaptation on the British Guy Fawkes Day? Would this explain why the practice was so heavily prevalent in British slave colonies and why it travelled so freely?

Africa is but a piece in a larger puzzle

In the mystery that is John Canoe, Africa is merely a piece in a larger more complex puzzle. One problem we have with the John Canoe, the Merry Andrew, the Jumby and the Aunt Sally, is that we know almost nothing concrete about them. These figures, in negro sensibilities, appeared one day in history, took off like wild fire, and their connection to those of African descent, in English speaking colonies, like Belize, Jamaica, British Honduras, Trinidad and Bahamas, became unwaveringly attached.

Another problem is why so many have not even considered how the traditional customs of the English colonies themselves, may have influenced it all. John Canoe could be a concoction taken from the English tradition of effigy burning of Guy Fawkes Day. Guy Fawkes was celebrated by the English, on everyone of their West Indian colonies. Could this have given birth to John Canoe?

A problem of message transportation is also curious to the John Canoe history. Who took the message of John Canoe to the various islands and to America? The only people who travelled freely back then were white people. Slaves didn’t travel like that, they didn’t communicate like that and why would they even care if John Canoe was happening on Cat Island or Jamaica or South Carolina, when all they were trying to do was survive slavery?

And curiously by the early 1800s, as the transatlantic trade was coming to an end, Africans liberated onto Bahamian shores, did not have the legend of John Canoe burning on their lips. If Canoe was some beacon in African legend, why didn’t these groups, in a new era, come with the story of this supposed hero as well.

What we do know, the bread crumb trails, the innocuous references made by the only people who could read and write hundreds of years ago, the slave merchants and chattel traders, all seems more like a series of wobbly leaps across time and oceans. A bit of conjecture here, and there, rather than exact historical movements and attachments. We can’t blame them really. To be fair, the way slaves whiled away their Christmas break from the fields was of no real concern at that time. As long as they were not plotting insurrection, absenting themselves or stealing, all was well.

Let’s take a look at some of the characters which were and had been predominant in the lives of negroes in the West Indies.

In 1886, a writer for the New York Times sought out an expert on negro culture in the West Indies. From this we learn of curious characters like Jumby and Aunt Sally.

The Jumby (The Ghost)

“Did you ever hear of a Jumby dance?” Mr. Smith continued. “I need not ask whether you ever saw one, for I am sure you never did. They are very scarce and hard to find. ‘Jumby, I suppose you know, is another name for ghost, like Duppy. These dancers are so hard to find out that I have never seen one, though I have made efforts. But a friend living on an out of the way plantation managed to be admitted to one, and he gave me a very good description of it. Such dances are always held in some secluded place, where there is little danger of interruption. Generally you will find them in a negro house in the midst of a jungle, where nobody is likely to go by accident. There were at this one about 20 Africans, of both sexes. It was held in a wretched shanty house in the high woods. The people wore as few clothes as possible, with necklaces or sharks teeth, called bones, dried frogs and beads. Some of the men, wearing only what we would call swimming trunks had their bodies painted to represent skeletons. The shanty was dimly lit it with half a dozen candles, and in the middle of the floor was the Jumby, a sort of life-size idol with the body of a man and a head of a cock. He was an object of the deepest devotion and was treated with great respect. The dancers all remained outside till a signal was given, and then they entered, and the leader began to sing and African song, accompanying him self with an instrument called the tom-tom. He was an object of the deepest devotion and was treated with great respect. The dancers all remained outside till a signal was given, and then they entered, and the leader began to sing an African song, accompanying himself with an instrument called the tom-tom. As soon as he got underway here quick and the time, and in a moment one of the women sprang into the middle of the floor, in front of the gym be, and began to dance furiously, keeping good time with the music. A man joint her; and presently another couple sprang out, and another, and another, till the floor was full of dancers. Gradually the lights were put out, one after another, till only one candle remained burning, giving just light enough to make the dusky forms visible. The music continually grew and faster, until all the dancers will whirling like tops. Through all the apparent confusion the Jumby was kept in the middle of the floor, and was not once touched. This dance continued for hours, and did not break up till long after midnight.”

(Saturday, 08 May, 1886, The Advocate, Westminster, Maryland)

Obeahism, John Canoes and Aunt Sally

I will quote Mr. Webster’s definition of it: – “Obeah — A species of witchcraft practices among the West Indian negroes, and supposed to have been introduced from Africa.”

I had heard it before, I suppose, a thousand times; it would be hard to travel much in the west Indies without hearing of it. But it is equally hard to get any trustworthy information about it. Every white West Indian knows that it is a species of witchcraft practised by the Negroes, and sometimes a dangerous species, that has caused many a white man his life; but just how it operates very few people can tell. The Negroes know anything about it I will afraid to talk about it; and a large majority of them only know that it is a dangerous thing for them to meddle with, without having any definite idea of where the danger lies. I must say that in travelling nearly all over the West Indies I have never come across a single instance of any person being poisoned or injured by an Obeah man,” but I have read and heard of a great many instances, for the Obeah works by frightening the ignorant and poisoning those who are in his way.

(Saturday, 08 May, 1886, The Advocate, Westminster, Maryland)

“And, after all you cannot have a very definite idea of Obeahism. It is such an indefinite thing itself and it is difficult to give any definite description of it. The amount of the matter is, Negroes are so constituted that they must have something tangible to worship and believe in – something they can see and feel. They are wonderfully fond of stuffed figures. Nearly all their ceremonies have a bigger worked in some shape or another. For instance, look at the ‘John Canoes.’ They really have a festival with out a John continue, the staff figure of a man, that is treated with great respect. Sometimes they have two of them, which they consider father and son – John Canoe senior and John Canoe Junior. If John is by any possibility left out Aunt Sally is substituted.”

(Saturday, 08 May, 1886, The Advocate, Westminster, Maryland)

She is the same as John, only, being a woman, she is not treated with the same respect. She is carried to the place of merrymaking, laid out on a board, like a corpse, amid cries of ‘Here comes Aunt Sally; poor Aunt Sally! She’s dead.’

They take wonderfully to celebrating Guy Fawkes’ Night, (though they have no idea who Guy Fawkes was, and always call him Guy Fox,) because that gives them a chance to have an effigy, which they burn.

They are the most superstitious people in the world. There are certain trees in the West Indies that no negro could be induced or compelled to cut down for fear of some harm coming to him. Other kinds of wood they will not burn. If they catch a snake in the chicken yard they will kill it and burn it, and that, they think, will prevent any other snakes coming and killing the fowls.”

“Is the condition of the West Indian Negroes improving?” I asked. “Have freedom and education made them any less superstitious? “

“Well,” was Mr Smith’s cautious reply, “you see what they are now. They have been free in our West Indian colonies for nearly half a century, and for half of that time good schools have been in operation.”

(Saturday, 08 May, 1886, The Advocate, Westminster, Maryland)

The tale of the two possible Johns

John Canoe, the slave who escaped

A popular fable to explain the origin of John Canoe, which has been passed along, is the mythical story that a slave named John Canoe, managed to escape his master, at some point after the middle passage. Where, when and how is all conjecture and implausible at best.

The implausible nature of the clever John Canoe comes from the very story itself. It has no real identity, complexity or completeness. To suppose that it was passed from colony to colony, even to America, becoming a source of imaginative inspiration, when untold numbers of slaves ran away, staged uprisings and revolts without ever becoming local, much less international legends, is a lot to seriously consider.

John Conny – wealthy African chief, slave trader and collaborator.

John was probably not his name. His name was Conny. John may have been a title of sorts, a familiar name given to Africans who were friendly, influential chiefs or a Big Man who helped in the slave trade and procuring things for the European slave traders. It was said that the Europeans would give the African a name from their country, thereby making the African feel important.

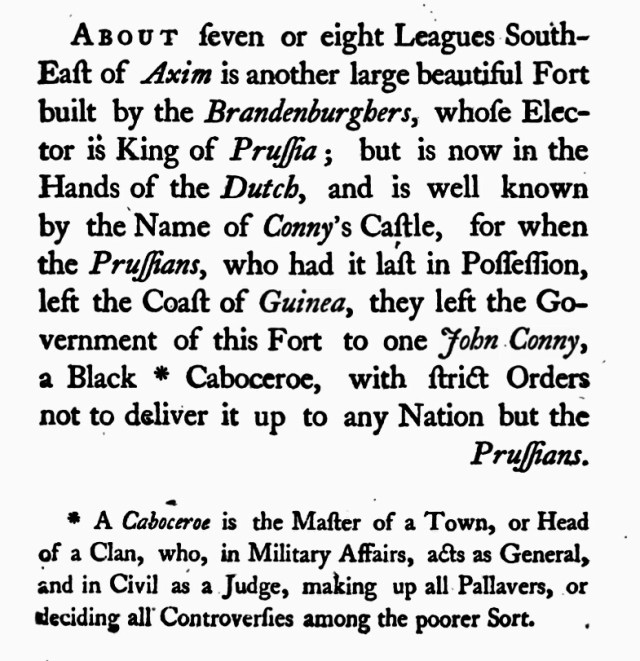

John Conny was a Big Man, a Caboceiro, a Don, a Jack or Tom. John may be just an English spelling of a Prussian (German) title given to Conny. He worked for the Brandenburg African Company and lived at the Brandenburg Fort on the Guinea Gold Coast in the early 1700s.

Another story about the origins of John Canoe centre on him fighting off the Dutch after the Prussians had sold the Brandenburg Fort on the Guinea coast, to them. Conny was living in it, keeping it safe for the Germans.

The story supposedly is that news of his fighting with the Dutch got back to Jamaica and he became a legend to Jamaican slaves.

The glaring question is of course, why would Jamaican slaves celebrate a known African slave trader, who not only ordered their capture but collaborated with the very people who had enslaved them, and inflicted so much misery on them?

(William Smith new voyage to Guinea: describing the customs, manners, soil, manual arts, agriculture and trade 1726)

Another book gives more of an account of John Conny and discusses another black African slave trader named John Corrente.

(Willem Bossman, New and Accurate Description of the Coast of Guinea, Divided into the Slave, Gold and Ivory Coast, 1705)

What was a Merry Andrew?

In 1670, a Merry Andrew was a type of clown, a buffoon. It was a person who entertained others by way of comic antics and Tom foolery. In ancient roman times, the Merry Andrew was a slave. John Canoe was considered a Merry Andrew, because after slavery, during John Canoe Day, negroes would do tricks, play music on makeshift instruments and dance in the hopes of gaining favour for street money. Kids and women would follow the John Canoes and beg for coins. Or coins would be thrown to the John Canoes, the Merry Andrews by passersby sometimes eager for them to quickly be on their way.